“I don’t really think that art really does that much in terms of any kind of social change. . . . I think it always remains a selfish outlet for the individual. And even though they’ve thought up kinda nice words for people who try to be creative, the truth is, that if you try to be creative, you really have to be a very selfish, ego-centered person who has this ego to believe that if you do an apple it will convey something that the millions of people who paint apples all the time do not.”[1]

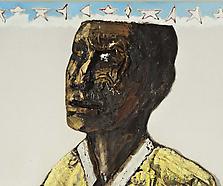

Benny Andrews (1930-2006) was born to a family of ten children to George and Viola Andrews in Plainview, Georgia, a rural farming community near Madison. For the first thirteen years of Benny’s life, his family lived and worked on land owned by the Orr family, which had built its fortune on the labor of slaves before the Civil War. As many historians have pointed out, Andrews’ family history reflects the contradictions regarding race relations in the United States. His paternal great-grandfather, William Jackson Orr, had been an officer in the Confederate Army, and his paternal grandfather, James Orr, spent over fifty years in a relationship with Jessie Andrews, Benny’s grandmother. Andrews’ father, George, worked as a sharecropper on Orr family land. Thus, Andrews was born into a system that closely resembled the system of slavery that had held his ancestors.

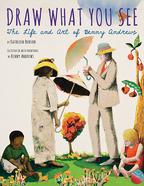

Despite the brutality of sharecropping, Andrews recalled his childhood as a happy one. In 1935, the family built and moved into a two-room wood-frame house on Orr land. Andrews began working in the fields as a young child, but he also attended the Plainview Elementary School, a one-and-a-half-room log cabin built by the black community in Plainview. Following in the footsteps of his father, a self-taught artist, Andrews began drawing at the age of three; by the time he was in elementary school, he had started to create his own comics. In 1943, the Andrews family moved to Madison to work on land managed by C.R. Mason. Because education beyond the seventh grade was strongly discouraged, Viola Andrews, who was determined to provide an education for her children, worked out an arrangement with the Mason family that enabled Benny to attend school when it was not possible to work in the fields. Andrews enrolled at Burney Street High School, graduating in 1948. Through a small amount of funding from a 4-H Club scholarship, Andrews was able to attend Georgia’s Fort Valley State College. However, his scholarship ran out after two years, and Andrews was disappointed with the lack of opportunities to study art. He left Fort Valley and enlisted in the United States Air Force, serving in the Korean War and attaining the rank of staff sergeant before receiving an honorable discharge in 1954. With funding from the GI Bill, Andrews enrolled at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. In 1958, he completed his Bachelor of Fine Arts degree and moved to New York City.

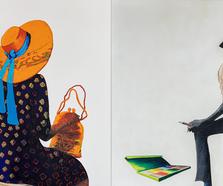

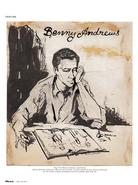

In New York, Andrews lived on Suffolk Street, where he met and befriended other Lower East Side figurative expressionists, including Red Grooms, Bob Thompson, Lester Johnson and Nam June Paik. He frequented local bars, jazz clubs, and coffee shops, drawing and painting his surroundings. By the 1960s, Andrews had mastered his “rough collage” technique, explaining, “I started working with collage because I found oil paint so sophisticated, and I didn’t want to lose my sense of rawness.” In 1962, Bella Fishko invited him to become a member of Forum Gallery, which held his first New York solo exhibition. Additional solo exhibitions at the gallery followed in 1964 and 1966. In 1965, with funding from a John Hay Whitney Fellowship, Andrews traveled home to Georgia and began working on his Autobiographical Series. In 1966, Andrews was featured in an exhibition with fellow figurative painter Alice Neel at the Countee Cullen Regional Branch of the New York Public Library in Harlem. Both activists concerned with inequality and injustice, they formed a close and lifelong friendship. They also painted portraits of each other: in 1972, Neel completed Benny and Mary Ellen Andrews, which is currently in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, and Andrews painted his Portrait of Alice Neel in 1985.

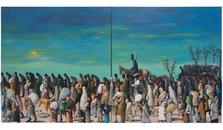

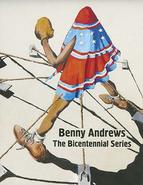

In 1970, Andrews began working on the Bicentennial Series as a response to the national celebrations planned for the bicentennial of the Declaration of Independence. Skeptical of the national mood of celebration and nostalgia, Andrews worried about whether the voices of contemporary African Americans would be included as part of the planning. He also feared that black Americans would be omitted from the official forms of national remembrance, or, conversely, that they would be included, but that the considerable contributions of African Americans to US history would be defined exclusively in terms of slavery. In his journal, Andrews described this project as “a Black artist’s expression of how he portrays his dreams, experiences, and hopes along with the despair, anger, and depression to so many other Americans' actions.” The Studio Museum in Harlem presented the first completed works of The Bicentennial Series in 1971. In 1975, the High Museum of Art in Atlanta presented four subseries from The Bicentennial Series; the exhibition traveled to the Herbert F. Johnson Museum, Cornell University, in Ithaca, NY and the National Center of Afro-American Artists in Boston. In 2016-17, Michael Rosenfeld Gallery presented Benny Andrews: The Bicentennial Series, which included the paintings and drawings for the six individual subseries that make up the whole body of work—Symbols, Trash, Circle, Sexism, War, and Utopia.

A self-described “people’s painter,” Andrews focused on figurative social commentary depicting the struggles, atrocities, and everyday occurrences in the world. His co-founding in 1969 of the Rhino Horn Group (along with Jay Milder, Peter Passuntino, Nicholas Sperakis, Peter Dean, Michael Fauerbach, Bill Barrell, Leonel Gongora, and Ken Bowman) affirmed his commitment to figural work even as various abstract movements gained ascendancy. However, in his mind, art was no substitute for action. To that end, Andrews also embarked on a long career as an educator, activist, and advocate. In 1968, he began teaching at Queens College, City University of New York, where he was part of the college’s SEEK (Search for Education, Elevation and Knowledge) program, designed to help high school students from underserved areas prepare for college. In 1969, he became a founding member of the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition (BECC), which formed coalitions with other artists’ groups, protested the exclusion of women and men of color from institutional and historical canons, advocated for greater representation of black artists, curators, and intellectuals within major museums, and facilitated art education. In 1971, the art classes Andrews had been teaching at the Manhattan Detention Complex (“the Tombs”) became the cornerstone of a major prison art program initiated under the auspices of the BECC that expanded across the country. In 1976, Andrews became the art coordinator for the Inner City Roundtable of Youths (ICRY)—an organization comprised of gang members in the New York metropolitan area who seek to combat youth violence by strengthening urban communities. That same year, he picketed the Whitney Museum’s John D. Rockefeller III Exhibition of American Artists, which claimed to exhibit 300 years of American art, but contained not a single work by a black artist and only one (white) woman. From 1982 to 1984, he directed the Visual Arts Program, a division of the National Endowment for the Arts (1982-84), initiating a project to enable artists to obtain health insurance. In 2002, the Benny Andrews Foundation was established to help emerging artists gain greater recognition and encourage artists to donate their work to historically black museums. Shortly before his death in 2006, Andrews was working on a project in the Gulf Coast with children displaced by Hurricane Katrina.