“I am interested in the social, even the propaganda, angle in painting; but I feel that the job of everyone in a creative field is to picture the whole scene. . . . I am interested in creating a style that is much more powerful, that will take in the technical end and at the same time will say what I have to say. Paint is the only weapon I have with which to fight what I resent. If I could write, I would write about it. If I could talk, I would talk about it. Since I paint, I must paint about it.”[1]

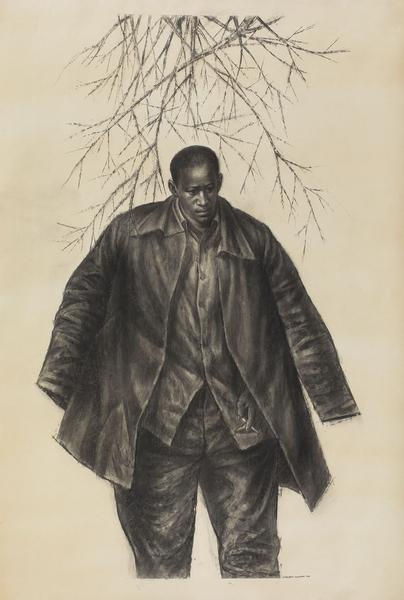

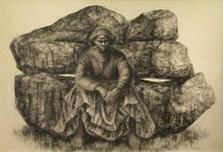

Charles White is one of the great interpreters of the human experience who, over the course of his five-decade career, executed an astounding body of paintings, drawings, prints and murals depicting African American life, history, and culture. He executed portraits of historical figures and leaders including John Brown, Sojourner Truth, Nat Turner, Booker T. Washington, and Frederick Douglass, as well as everyday African Americans from all walks of life including field workers, factory workers, soldiers, preachers, musicians, children, and mothers. The fortitude, endurance, and strength of the human spirit captured in his images counteracts racist stereotypes and advocates for action against inequality. From his early traditional works to his experiments with modernism, White’s social realist concerns and dignified portrayal of his subjects persist throughout his oeuvre.

Charles Wilbert White III was born in Chicago, Illinois in 1918.[2] His mother, Ethelene Gary, was a domestic worker who had moved to the city from Mississippi four years earlier. White’s father, Charley, held several jobs, and although he did not live with Charles and Ethelene, the family saw each other regularly and attended church together weekly. When Charles was a child, Ethelene would drop him off at the public library or the Art Institute of Chicago while she ran errands. These early experiences instilled in Charles a love of reading and art that his mother encouraged. She bought him his first set of oils when he was seven, and after a few mishaps (including taking down some of his mother’s window shades to use as canvas), Charles learned how to mix his paints by watching a group of art students in a nearby park. In 1926, Charley White died and Ethelene married Clifton Marsh, an abusive alcoholic. At the age of nine, Charles began working to help support his family in addition to attending school. Around this time, he also began taking long trips to Mississippi, where he learned about the history of his family and fell in love with Southern Black American culture.

Charles White’s talent was recognized at an early age. In seventh grade, he was one of five hundred Chicago public school students to receive a scholarship from the James Raymond Nelson Fund to attend Saturday art classes at the Art Institute of Chicago. Along with painter Eldzier Cortor (1916-2015) and Margaret Burroughs (1915-2010), White continued to take classes at the Institute until his junior year of high school, receiving instruction and attending lectures by such artists as Ivan Albright (1897-1983). Outside of the institute, White participated and exhibited with the Art Crafts Guild, which counted Charles Sebree (1914-1985), Richard Wright (1908-1960), Gwendolyn Brooks (1917-2000), and other luminaries of the Black Chicago Renaissance among its members.

Although White was spared the discrimination of the Jim Crow South, the Chicago of his youth was still a starkly divided city that regularly exposed him to racism. At age fourteen, White read Alain Locke’s The New Negro, which sparked a sense of pride and a passion for Black American history. This caused problems for him at school, as the teachers deemed him a troublemaker for questioning the school’s Eurocentric curriculum. He won scholarships to study art in 1934 and 1935 which were rescinded when the awarding institutions learned that he was Black. Finally, in 1937, White received—and was able to collect—a scholarship to attend the Art Institute of Chicago.

The following year, White joined the Works Progress Administration (WPA), first as an easel painter and then in the mural division, where he soon discovered that Black artists had to fight for equal treatment within the program. Despite its discriminatory power structure, however, White was given the opportunity to create his first mural after less than a year. In late 1939, he completed Five Great American Negroes, a five-by-twelve-foot canvas depicting Sojourner Truth, Booker T. Washington, Frederick Douglass, Marian Anderson, and George Washington Carver. The following year he was commissioned by the Associated Negro Press (ANP) to create another mural, A History of the Negro Press, for the American Negro Exposition at the Chicago Coliseum, and a selection of his works on paper were included in the Exposition’s art show, Exhibition of the Art of the American Negro, 1851 to 1940, organized by Alain Locke. While in the WPA, White also met and befriended photographer Gordon Parks (1912-2006), and the two of them would often walk through Chicago’s South Side together, photographing and sketching daily life in the neighborhood.

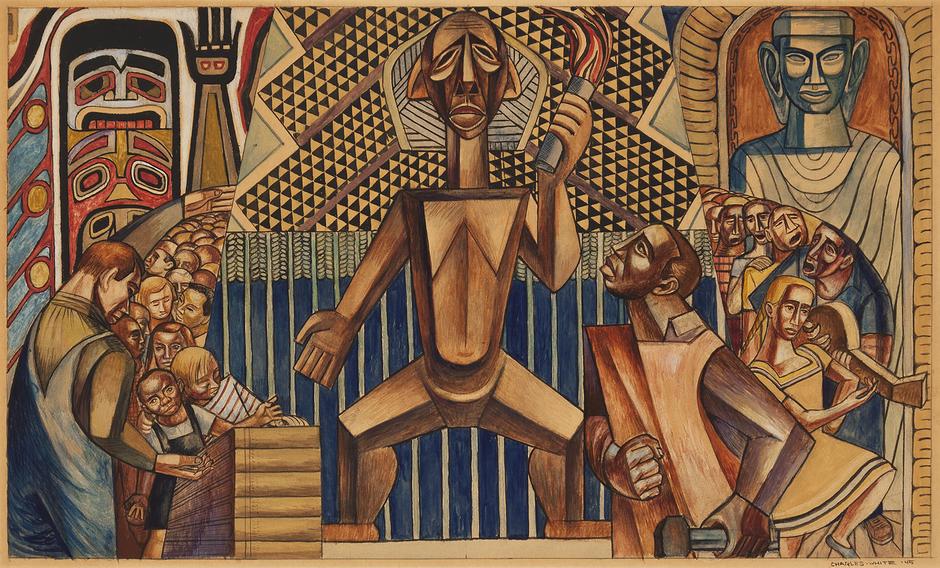

The 1940s were eventful years for White. In 1941, he met and married Elizabeth Catlett (1915-2012) and moved to New Orleans, taking a teaching position at Dillard University, where Catlett was chair of the art department. A Julius Rosenwald Fellowship in 1942 enabled White to move to New York City and study at the Art Students League with Harry Sternberg, and then travel throughout the South, conducting research for his next mural, The Contribution of the Negro to Democracy in America at the Hampton Institute (now Hampton University) in Hampton, VA. With the funds from an additional Rosenwald Fellowship awarded in 1943, White spent a year creating the mural. At Hampton, he met and befriended art professor Viktor Lowenfeld (1903-1960) and his student John Biggers (1924-2001). After returning to New York in 1944 to teach at the George Washington Carver School, he was drafted into the U.S. Army, serving as a corporal in the all-black 132nd Engineering Regiment. He was honorably discharged eight months in after contracting tuberculosis, a disease that would compromise his health for the rest of his life.

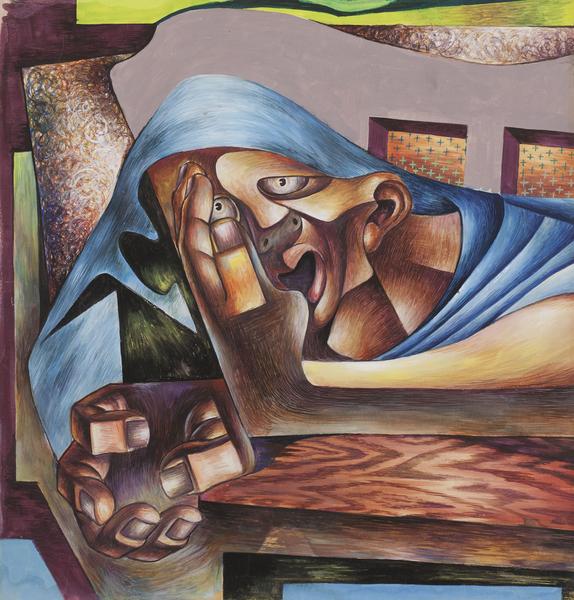

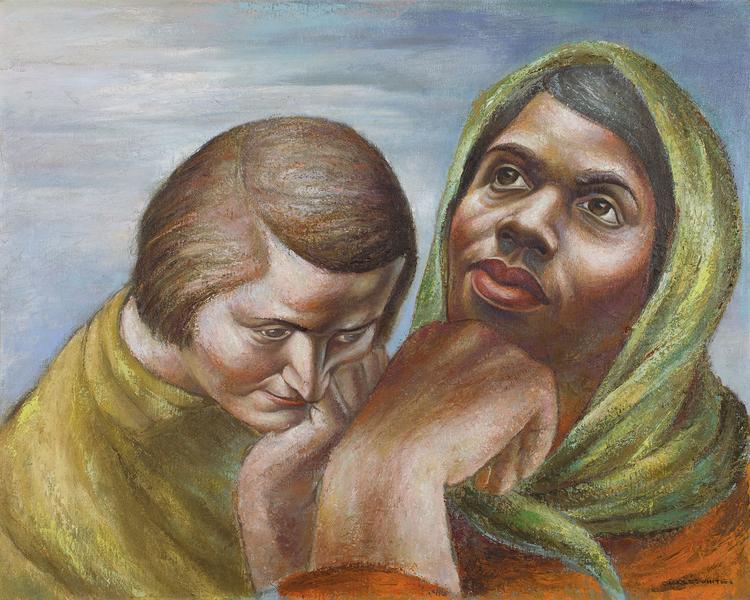

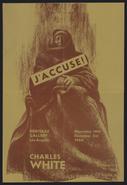

White was interested in Mexican mural painting, and in 1946 he and Catlett moved to Mexico City so he could take a job at the Escuela Nacional de Pintura y Escultura and join the famed graphic arts collective Taller de Gráfica Popular. White and Catlett returned to the Northeast the following year, where they divorced. The same year, The American Contemporary Art (ACA) Gallery in New York mounted White’s first solo exhibition, a series of works depicting the strength and beauty of real and archetypal Black American women. Over the course of several months in 1948, White underwent several operations at Saint Anthony’s Hospital in Queens to treat his ongoing health issues from tuberculosis. In 1950, he married Frances Barrett, a social worker he met while a summer camp counselor at Wo-Chi-Ca (short for Workers Children’s Camp), an interracial, coed camp founded in Hunterdon County, NJ by the International Workers Order.

With the rise of McCarthyism after World War II, the FBI had begun a surveillance file on White. Although he never joined the Communist party, White's political inclinations and his friendships with leftist artists and intellectuals eventually led to his being called to testify at the hearings of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). Fortunately, for mysterious reasons, White was just as suddenly informed that his testimony was no longer needed. Undaunted, White continued to advance a politics of struggle in his art, creating ennobling portrayals of historical figures such as Sojourner Truth and Harriett Tubman and depicting ordinary black farmers, preachers, mothers, and other workers in a dignified manner that reflected their grace and strength. By this time White was working almost exclusively with charcoal or sepia-toned oil on paper. White received numerous awards throughout the 1950s, including a John Hay Whitney Foundation Opportunity Fellowship (1955–56) and his first monograph, Charles White: Ein Künstler Amerikas by Sidney Finkelstein (VEB Verlag der Kunst, 1955).