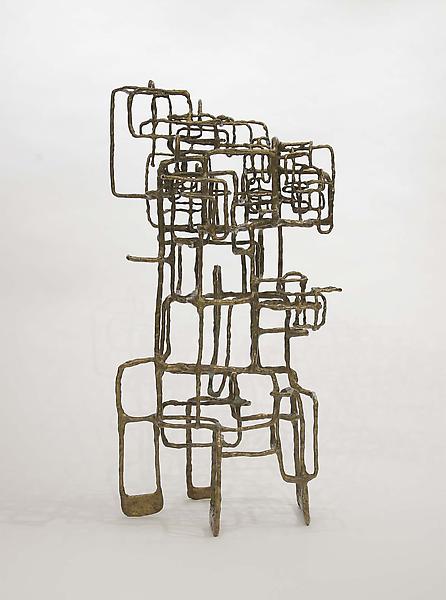

“All day long, I observe Nature; people walking in the street the movements of branches in the wine, the patterns made by neon signs and auto headlights on a wet night; marvelous cracks in the pavements; and equally, the range of one’s own feelings; the whole complex of both ‘outer’ and ‘inner’ reality . . . While I am welding a sculpture, no conscious ideas intrude themselves into the work, I have eyes only for the reality of what happens before me.”[1]

Born in Alexandria, Egypt in 1913 to Russian parents, Ibram Lassaw discovered his love for sculpture at a young age. When he was a child, his family moved throughout North Africa and the Mediterranean, and Lassaw lived in Tunis, Malta, Naples, Marseille, and Istanbul before the family finally settled in Brooklyn, New York in 1921. In 1926, Lassaw took clay-modeling classes with Dorothea Denslow at the Brooklyn Children’s Museum. While he was in high school, he continued to study sculpture, at the Beaux-Arts Institute of Design, where he learned to model from life. After his graduation in 1931, Lassaw enrolled in courses at City College. However, he dropped out after a year, opting to pursue his interest in the arts full-time instead. He organized and served as treasurer for the Unemployed Artists’ Association, participated in the Public Works of Art Program, and joined the Federal Arts Project of the WPA, as a teacher and sculptor. During this time, Lassaw worked on his own sculptures in the various studio spaces he held. In 1933, he made his first abstract sculpture and abandoned figural representation entirely. In the late 1930s, Lassaw bought a power jigsaw and also began brazing metal rods. In 1938, he made a series of “wooden shadow boxes with hidden electric bulbs to illuminate the interiors. These works, which combined objets trouvés, wooden elements and painted metal shapes, were an innovative fusion of biomorphs with László Moholy-Nagy’s ideas for light-space constructions.”[2] Lassaw’s passion for abstraction led him, in 1937, to organize the American Abstract Artists group (AAA), an artists collective focused on promoting abstract art through cooperative exhibitions.

In 1942, Lassaw enlisted in the army, where he trained as a welder. Although the two years he spent in the armed forces impeded his work with the AAA, the skills he learned would be central to his sculpture a decade later. In 1949, Lassaw became a founding member of The Club—the group of artists, writers, and art dealers who met in an apartment at 39 East 8th Street—and in 1950, he was included in MoMA’s Abstract Painting and Sculpture. Lassaw joined the Kootz Gallery’s stable of artists, and the first sale of his sculptures in 1950 enabled him to buy equipment for oxyacetylene welding, which he began to use for sculpture in 1951. Like contemporaries Richard Hunt and Herbert Ferber, Lassaw strove to create truly three-dimensional sculpture, and in his work, negative space became a vital part of the overall composition. As with many artists of his generation, including Claire Falkenstein, this interest in the