“The artist…cannot take flight to the Elysian Fields of the preciousness of perfection, the prism of the eye, but has to deal with matter complex.”[1]

“Abstraction is no longer enough for me. So I am returning to the image. The image gives me a wider sense of communication.”[2]

A prolific artist who applied the principals of gestural abstraction to figurative painting, Jan Müller was born in Hamburg, Germany in 1922 to Heinrich and Lisa Müller, socialists who opposed the Nazi regime. When Müller was a child, his father was arrested for campaigning against Hitler. Upon his release from custody in 1933 (thanks to friends who bribed officials), the family fled Germany for Czechoslovakia. They stayed in Prague for five months, leaving as the city was unable to handle its already substantial population of German refugees. Between 1933 and 1941, Müller and his family were often separated as they traveled in search of safety and stability. Heinrich went to Paris, while Lisa took the children to Bex-les-Bains, a Swiss town near the French border, where she was able to find work teaching at a boarding school. In Switzerland, Müller had his first bout of the rheumatic fever that would plague him throughout the rest of his life and ultimately kill him. In 1936, the family moved to Amsterdam, and two years later, Müller and his older sister, Ruth, went to Paris. After the invasion of Poland in 1939, France declared war on Germany, and in May 1940, Müller was transported to an internment camp in Lyon. Two months later, when Paris fell to the Germans, Müller fled to Spain and then to Portugal before he was able to reach the United States. Ruth left soon after, but Lisa and Müller’s younger sister, Maren, would not be able to join them until after the war.[3]

Müller arrived in the United States in 1941, but would have to travel to Canada from time to time in order to renew his visa. After some time working on a farm in Ohio, he eventually settled in New York, where he held a variety of jobs—as a dishwasher, in a pen factory, and as a film cutter—until 1945, when he decided to become a full-time artist. In her brief biography for the posthumous Guggenheim exhibition of Müller’s work, his widow, Dody, notes that Müller saw each of these jobs simply as a means to an end—being able to afford to paint. But his experience working in film editing, of cutting celluloid and “putting together the various frames of film…was later to influence his use of ‘close-ups and ‘long shots’ in the triptychs and hanging pieces. He was intrigued by the movies and would spend much time there. The whole experience of paying for a ticket at the box office, entering the black movie house, the movies themselves, the people inside, was of endless fascination to him.”[4]

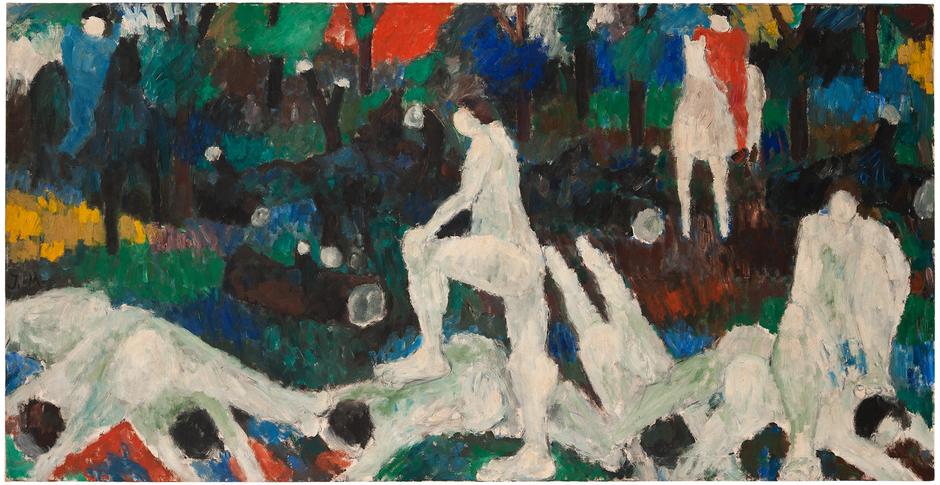

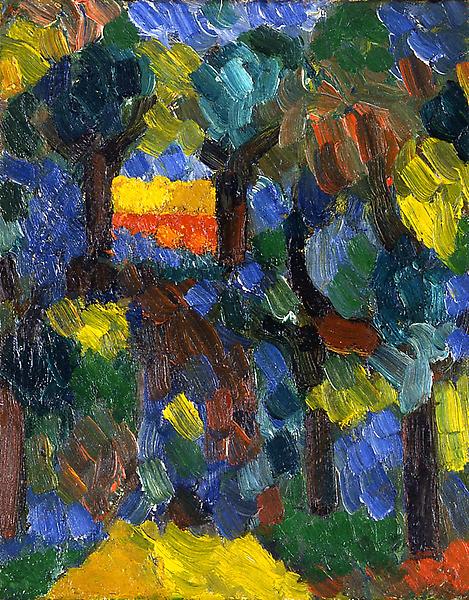

In 1945, Müller took classes at the Art Students League, but left after six months to study at the Hofmann School of Fine Art, at 52 West 8th Street. Run by Hans Hofmann, whose reputation as an excellent teacher was well-established, the Hofmann School had become a vital space for nurturing and developing the talent and ideas that formed the foundation of abstract expressionism and the New York school of painting. Although Hofmann and Müller often had passionate disagreements about painting, the two were quite fond of each other and developed a close, father-son bond. In the late 1940s, Müller began creating his “mosaic” paintings—abstract works comprised of small, irregular, patches of vivid color that were mostly square or round in shape. He continued to adapt and transform this style through the early 1950s, moving away from more explicit explorations of Hofmann’s “push-pull” theories of color toward compositions that operated on a tension between abstraction and figuration. Sometime around 1952, Müller’s vivid palette became more subdued, and these “touches of color, sometimes elongated into strokes, [began to] run in lines which converge and swirl together, activating the large canvases with dynamic patterns of motion and light…in which the small, roughly blocked-in figures emerge from the formless universe as frail substances which challenge the engulfing chaos.”[5]

In the early 1950s, Müller lived and painted in a sparse, unheated studio on Bond Street in lower Manhattan. He also spent summers in the vibrant arts community of Provincetown, Massachusetts, the site of Hofmann’s summer school as well as the summer destination for such painters as Lester Johnson, John Frank, Robert Motherwell, and later, Bob Thompson. Although Müller would later be able to earn a living exclusively from the sale of his paintings, in 1951, he had trouble getting galleries to exhibit his work, as did many young artists who found themselves outside or on the edges of abstract expressionism. As a solution, he co-organized an exhibition, together with Wolf Kahn and Felix Pasilis, on the top floor of 813 Broadway, where Kahn and Pasilis had studios. Simply titled 813 Broadway, the exhibition drew hundreds of artists and visitors as well as some favorable critical attention. The success of 813 Broadway inspired Müller, Kahn, and Pasilis to establish a cooperative gallery together with Richard Stankiewicz, Barbara and Miles Forst, Allan Kaprow, and Jean Follet, among others. In the fall of 1952, the Hansa Gallery opened at 70 East 12th Street. The gallery’s working name was Dodeca, but “Kahn and Müller, both refugees from Hitler’s Germany, soon proposed a different name, Hansa. It dually referenced the Hanseatic League, a medieval confederation of free cities joined together for mutual benefit (hansa means ‘fellowship’ in medieval German), and cleverly honored their teacher and friend, Hans Hofmann.”[6]