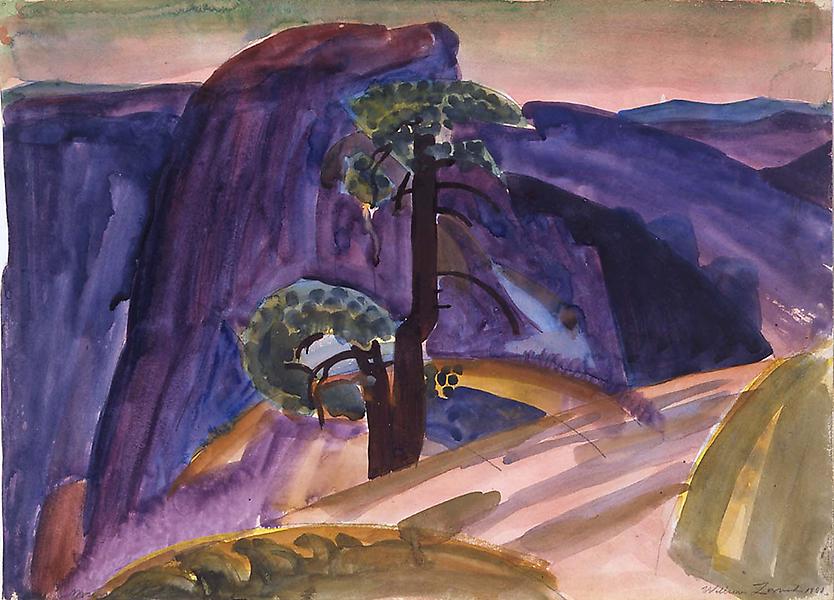

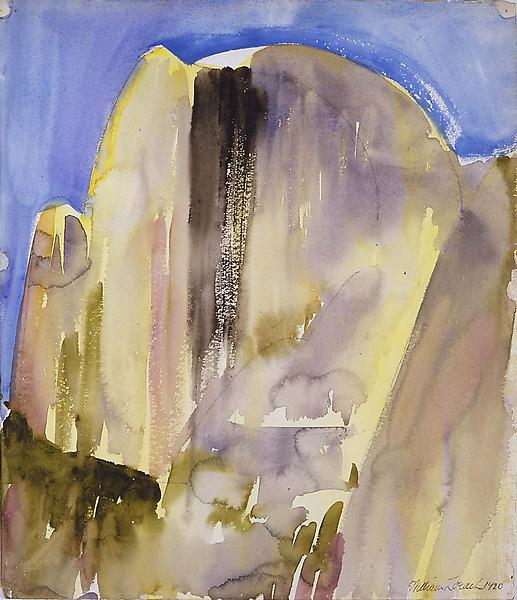

One of the first artists in the United States to employ the sculptural technique of direct carving, William Zorach was born Zorach Samovich in Eurberick (now Jurbarkas), Lithuania in 1889. When he was a child, his family emigrated to the United States, settling in 1891 in Cleveland and changing the family name to Finkelstein. In grammar school, Zorach’s name underwent a second transformation when his teacher dubbed him William. Zorach’s parents struggled to feed their ten children, and when he was a teenager, Zorach dropped out of school to work for a commercial lithography firm, while taking night classes at the Cleveland Art School. In 1908, Zorach left Cleveland for New York City and enrolled in courses at the National Academy of Design. Two years later, he traveled to Paris, where he studied at the cutting-edge Académie de la Palette with John Duncan Fergusson and Jacques-Emile Blanche and met Marguerite Thompson, an American artist who had been in Paris since 1908. Zorach was a talented painter, but his style remained academic; Thompson helped him to find his own artistic vision. In 1911, Zorach participated in the Salon d’Automne, and the following year, the couple moved back to the United States and married. They settled in New York’s Greenwich Village, where, because neither artist had gallery representation, they held exhibitions in their home, which they dubbed the “Zorach Studio.”(1) In 1913, he exhibited two works in The Armory Show.

Although Zorach had been trained in drawing and painting, he was self-taught as a sculptor. In 1917, he began experimenting with the technique of carving directly into wood; four years later, he added stone to his range of media. By 1922, Zorach had abandoned painting in oil but remained committed to watercolors while continuing to find his voice as a sculptor. Nature served as the inspiration for his sculptural works and his output was devoted to lyrical works of reclining female nudes and elegant stone faces and torsos influenced by Greek classicism as well as sculpture from Asia, the Pacific, and Africa. He began to exhibit regularly at the Downtown Gallery with Edith Halpert, and by the end of the 1920s, he started to gain national recognition for his art. In 1921, the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts had his first of four solo exhibitions and in 1929, Zorach began a thirty-year teaching career at the Art Students League. A founding member of the Sculptor's Guild, he was a visiting artist in 1946 at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture; he continued his affiliation with the school annually until his death.

William Zorach (1887-1966)

Exhibitions

New & Noteworthy

Prints & Publications

Artist Information

In addition to creating art, Zorach wrote, lectured, and participated in public debates. A proponent of what he called “national art,” Zorach believed that a work of art should express its immediate cultural context, even if over time it eventually acquired a universal quality.(2) Possibly as part of this belief, Zorach created several public murals in United States Post Offices and site specific sculptural commissions, including Spirit of the Dance (1932) for Radio City Music Hall in Rockefeller Center, his bronze Olympic Runner in Kiener Plaza in St. Louis, and Man-Made Power, a teakwood bas-relief for the Courthouse in Greenville, Tennessee.

Zorach’s art was celebrated throughout his life and after his death. In 1931, his Mother and Child won the Art Institute of Chicago’s Logan Prize, and in 1950, the Art Students League honored him with a retrospective exhibition. Nine years later, the Whitney Museum of American Art mounted a major retrospective of Zorach’s work. In 1968, two years after his death, and a year after the posthumous publication of his autobiography, Art Is My Life, the Brooklyn Museum held a major exhibition of his work. Most recently, the Portland Museum of Art mounted Marguerite and William Zorach: Harmonies and Contrasts. His work can be seen in numerous public collections throughout the United States including Art Institute of Chicago, The Brooklyn Museum of Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, and the Whitney Museum of American Art.

(1) Jessica Nicoll, “To Be Modern: The Origins of Marguerite and William Zorach's Creative Partnership, 1911-1922,” Portland Museum of Art. http://www.tfaoi.com/aa/3aa/3aa85.htm. Accessed May 2010.

(2) Mariquita Villard, “William Zorach and His Sculpture,” Parnassus, v.6 no.5 (October 1934), 3-6.