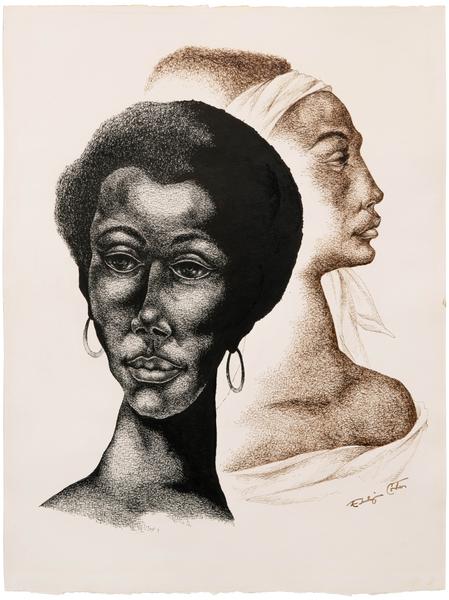

“The Black woman represents the Black race. She is the Black Spirit; she conveys a feeling of eternity and a continuance of life.”[1]

Celebrated for his serene paintings of graceful black women influenced by the elegant lines of African sculpture, Eldzier Cortor was born in Richmond, Virginia in 1916. His father, a successful electrician frustrated by southern racism, decided to move the family to Chicago in 1917. They first settled on the West Side, near the family of Archibald J. Motley, Jr. but changes in their economic status during the Depression forced them to move to the city’s South Side. Cortor grew up reading the Chicago Defender, a national weekly (at the time) newspaper focusing on and published by black Americans. The Defender campaigned against lynching and segregation, and it published the writing of such authors as Langston Hughes and Gwendolyn Brooks. But Cortor’s favorite section was a recurring comic strip featuring a hapless southern tramp new to Chicago, who eventually gathers enough money to travel to Africa.[2] As a teenager, he attended Englewood High School, where he met Charles Sebree and Charles White.

In 1936, Cortor enrolled at the Art Institute of Chicago, where one of his classes involved a trip to the Field Museum to see the collection of African sculpture. The dramatic attenuation of the human form and the dynamic body poses central to West African art had a tremendous impact on Cortor’s visual sensibilities. He continued his studies under László Moholy-Nagy at Chicago’s Institute of Design. During the 1930s, Cortor found work with the Federal Art Project of the WPA, and in 1941, with funds from the WPA, he co-founded the South Side Community Art Center on South Michigan Avenue. Three years later, Cortor received a grant from the Rosenwald Foundation, in order to travel to the Sea Islands off the coast of Georgia and the Carolinas and study the Gullah community there. Despite their traumatic history of diaspora and slavery, the Gullah had preserved West African language, food, religion, and traditions in the Americas for generations, often fusing African ways with European ones to create a unique culture. As such, they became a black American ideal for Cortor, and Gullah women were the inspiration for his visualization of the transcendent spirit of African Americans embodied as a quiet, regal woman of striking beauty wearing a vibrant headscarf.